|

|

|

|

|

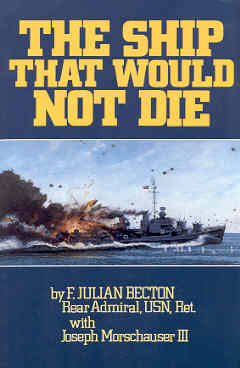

The Ship That Would Not Die

by F. Julian Becton with Joseph Morschauser III

Pictorial Histories Publishing, 1980, 295 pages

The destroyer Laffey fought for 80 minutes against 22 Japanese kamikaze planes and conventional bombers on April 16, 1945. Although the ship's gunners downed many incoming planes, seven suicide planes crashed into the ship, and two other planes dropped bombs on the ship. These attacks killed 32 and wounded 71, but Laffey survived despite fires, smashed and inoperable guns, and a jammed rudder. F. Julian Becton, Laffey's commander during World War II, wrote this thorough history of the ship's distinguished wartime service at Normandy, the Philippine Islands, and Okinawa. Joseph Morschauser III, a former writer for Look magazine, co-authored this book's 12 chapters that tell the story of the ship hit the most times by kamikazes in a single day.

Becton, while executive officer aboard the destroyer Aaron Ward, witnessed the sinking of the first destroyer named Laffey during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942. He later became commander of the Aaron Ward in March 1943, but his command lasted only three weeks before being sunk after five Japanese planes hit or nearly missed his ship with bombs. The Navy then assigned him to command the newly-built destroyer Laffey, commissioned in February 1944. He continued as commander of the ship until July 1945, after the damaged ship returned to the mainland for repairs. Becton became famous for his reply to an officer asking him whether they would have to abandon Laffey after several kamikaze planes had hit her. "We still have guns that can shoot. I'll never abandon ship as long as a gun will fire!" He continued to serve in the Navy after World War II and reached the rank of Rear Admiral.

Chapters 1 and 2 describe the sinking of the original destroyer named Laffey and Becton's assignment as commander of the new Laffey. Chapter 3 gives a description of the new ship being built at Bath Iron Works in Maine, and the next chapter covers the ship's shakedown training in Bermuda. Chapters 5 and 6 tell about Laffey's first battle assignment to provide support for the Allied invasion of France in June 1944.

Chapters 7 to 10 cover Laffey's participation in many Pacific battles from her arrival at Ulithi in early November 1944 to the beginning days of the Battle of Okinawa in early April 1945. The destroyer had numerous experiences with kamikaze planes during this period. The crew witnessed suicide crashes into other ships, shot at incoming planes, and provided aid to other ships that had been hit.